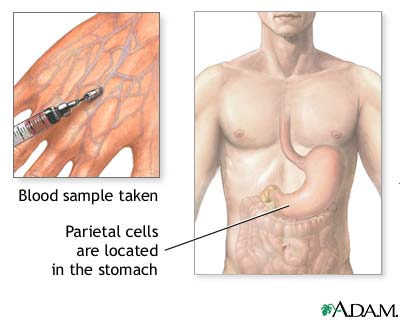

Anemia is a condition of reduced hemoglobin levels; pernicious anemia (also known as Addison’s anemia) is caused by a deficiency of or inability to use vitamin B12. Normally, vitaminB12 combines with the intrinsic factor, a substance that is secreted by the gastric mucosa, and then follows a path to the distal ileum, where it is absorbed and transported to body tissues. In pernicious anemia, intrinsic factor deficiency impairs vitamin B12 absorption. The deficiency of vitamin B12 inhibits the growth of red blood cells (RBCs) and leads to the production of insufficient and deformed RBCs with poor oxygen-carrying capacity. Because these deformed RBCs are known as megaloblasts (primitive, large, macrocytic cells), pernicious anemia is characterized as one of the megaloblastic anemias. Pernicious anemia is also caused by a deficiency of gastric hydrochloric acid (hypochlorhydria).

Complications caused by pernicious anemia include macrocytic anemia and gastrointestinal disorders. Pernicious anemia impairs myelin formation and thus alters the structure and disrupts the function of the peripheral nerves, spinal cord, and brain. Patients have a high incidence of benign gastric polyps, peptic ulcers, and gastric carcinoma. Low hemoglobin levels and consequent hypoxemia of long duration can result in congestive heart failure and angina pectoris in the elderly. If it is left untreated, pernicious anemia can cause psychotic behavior or even death.

Two causes lead to deficiency of vitamin B12: inadequate intake or poor absorption. Inadequate intake may result from dietary deficiencies. Failure to absorb occurs from a deficiency in intrinsic factor. Pernicious anemia is significantly more common in patients with autoimmune-related disorders, such as thyroiditis, myxedema, and Graves’ disease, which, in theory at least, decrease the hydrochloric acid production that is essential for intrinsic factor formation. Gastric resection can also result in the absence of intrinsic factor.

Nursing care plan assessment and physical examination

Because large stores of vitamin B12 are present in the body, signs and symptoms of pernicious anemia may not appear for some time. Ask the patient if he or she has experienced repeated infections. Elicit a history of severe fatigue, weakness, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, flatulence, diarrhea, or constipation. Ask the patient if he or she has experienced a sore tongue or heart palpitations or recent difficulties in breathing after exertion. Central nervous system findings are a hallmark of this anemia. Establish a history of sensory organ disturbance; ask the patient if he or she has experienced blurred or altered vision, altered taste, or altered hearing. Ask the patient if he or she has experienced numbness, tingling, lack of coordination, or lack of position sense. Ask male patients about recent experiences with impotence. Elicit any history of lightheadedness, memory lapses, faulty judgment, irritability, or paranoia. Elicit a complete history of medical conditions, especially autoimmune-related disorders, such as thyroiditis, myxedema, and Graves’ disease. Ask the patient if she or he has undergone a gastric resection or if any members of her or his family have had pernicious anemia.

The patient may appear listless. Note any premature graying or whitening of the hair. The patient may have waxy, pale to light lemon-yellow skin and jaundiced sclera. Inspect the patient’s mouth and check for pale lips and gums and a beefy, red, smooth tongue as a result of papillary atrophy. Note any incidence of leg edema. Weight loss may be apparent. Percussion or palpation of the abdomen may reveal an enlarged spleen and liver. You may note tachycardia and a rapid pulse rate. Auscultation of the heart may reveal a systolic murmur. Spinal degeneration may occur, and positive Romberg’s and Babinski’s signs may be a clinical finding.

Pernicious anemia produces a variety of distressing signs and symptoms, such as changes in the function of the sensory organs, dietary habits, excretory function, and sexual performance. Appearance changes may disturb the patient as well. Neurological complications may cause paranoia, disorientation, or delirium.

Nursing care plan primary nursing diagnosis: Altered nutrition: Less than body requirements related to anorexia, diarrhea, or achlorhydria.

Nursing care plan intervention and treatment plan

Primary intervention focuses on locating and correcting the contributing causes. Medical therapy centers around vitamin B12 replacement. Oral vitamin B12 is indicated for rare dietary deficiencies when intrinsic factor is intact. More often, vitamin B12 is given parenterally, but because of the risk of allergic reactions, it should be started slowly. A generally well-balanced diet with emphasis on vitamin B12–rich foods, such as animal protein, eggs, and dairy products, is important. Soybean milk may be offered as a source of vitamin B12 for strict vegetarians. A low-sodium diet may be imposed. Begin bedrest to combat fatigue. To reduce the cardiac workload, elevate the head of the bed and administer oxygen as ordered. Oral care may include antifungal preparations and special mouth rinses with hydrogen peroxide and salt water and topical anesthetics, such as magnesium hydroxide and viscous lidocaine, for mouth pain. Ensure that meals do not irritate the patient’s mouth by being too hot or cold or too difficult to chew.

Plan undisturbed rest periods to help the patient conserve energy. Provide a safe environment to prevent injury that is caused by neurological effects. Provide assistance for walking and activities of daily living if necessary. Provide a safe environment because fine motor skills are diminished and paresthesias and balance difficulties occur. Allow time each day to sit with the patient to talk about the response to the illness and to answer questions.

If the patient’s mouth and tongue discomfort make speech difficult, provide an alternate means of communication, such as a pad and pencil. Encourage fluid intake. Monitor dietary patterns carefully to determine if the patient is eating easily and tolerating meals.

Patient teaching and discharge planning are priorities. Teach the patient about the disease process of pernicious anemia and its chronic nature. Explore acceptable alternatives to activities of daily living that make living with pernicious anemia easier. Teach the patient to pace all activities and take rest periods. Encourage the patient to avoid extremes in temperature. Recommend that if the patient has developed problems with fine motor control, he or she may have an easier time dressing if clothing is designed without small buttons or hooks. Teach the patient and family to recognize and report immediately any signs of infection or complications (difficulty breathing, chest pain, dizziness, tingling in the extremities). Social service and home care referrals may be needed for follow-up.

Nursing care plan discharge and home health care guidelines

Teach the patient the relationship between vitamin B12 injections and the resolution of signs and symptoms of pernicious anemia. Instruct the patient how to self-administer a B12 injection, and establish a calendar for regular monthly injections. Discuss the need for a well balanced diet. Teach the route, dosage, side effects, and indications for use of medications. Instruct the patient to report any recurrent episodes of signs and symptoms of pernicious anemia. Patients with pernicious anemia are at risk for developing gastric carcinoma, so encourage twice-a-year complete physical examinations. If the patient has experienced permanent neurological disabilities, refer her or him to a physical therapist for an intensive program of rehabilitation.

No comments:

Post a Comment